- Home

- Bernard E. Harcourt

The Counterrevolution Page 3

The Counterrevolution Read online

Page 3

1

COUNTERINSURGENCY IS POLITICAL

THE COUNTERINSURGENCY MODEL CAN BE TRACED BACK through several different genealogies. One leads to British colonial rule in India and Southeast Asia, to the insurgencies there, and to the eventual British redeployment and modernization of counterinsurgency strategies in Northern Ireland and Britain at the height of the Irish Republican Army’s independence struggles. This first genealogy draws heavily on the writings of the British counterinsurgency theorist Sir Robert Thompson, the chief architect of Great Britain’s antiguerrilla strategies in Malaya from 1948 to 1959. Another genealogy traces back to the American colonial experience in the Philippines at the beginning of the twentieth century. Others lead back to Trotsky and Lenin in Russia, to Lawrence of Arabia during the Arab Revolt, or even to the Spanish uprising against Napoleon—all mentioned, at least briefly, in General Petraeus’s counterinsurgency field manual. Alternative genealogies reach back to the political theories of Montesquieu or John Stuart Mill, while some go even further to antiquity and to the works of Polybius, Herodotus, and Tacitus.1

But the most direct antecedent of counterinsurgency warfare as embraced by the United States after 9/11 was the French military response in the late 1950s and 1960s to the anticolonial wars in Indochina and Algeria. This genealogy passes through three important figures—the historian Peter Paret and the French commanders David Galula and Roger Trinquier—and, through them, it traces back to Mao Zedong. It is Mao’s idea of the political nature of counterinsurgency that would prove so influential in the United States. Mao politicized warfare in a manner that would come back to haunt us today. The French connection also laid the seeds of a tension between brutality and legality that would plague counterinsurgency practices to the present—at least, until the United States discovered, or rediscovered, a way to resolve the tension by legalizing the brutality.

In the late 1950s, Peter Paret, then a young PhD student in military history studying at the University of London under the supervision of Sir Michael Howard (one of Britain’s greatest military historians), became interested in the new French military tactics that were being developed and deployed in response to what had become known as “la guerre révolutionnaire.” Paret would eventually become a formidable historian best known for his research on Carl von Clausewitz. A professor at the School of Historical Studies at the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton, he became particularly renowned in strategic-studies circles as the editor of the second edition of Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, which remains a classic textbook for teaching the history of military strategy. But as a young scholar, Paret was one of the first people in the United States to discover, translate, and popularize the French doctrine of counterinsurgency warfare.

Paret practically coined the term “revolutionary warfare” for Americans in the early 1960s. He was introduced to the central tenets of insurgent revolutionary warfare, in his words, “during a stay in France in 1958.” He first wrote about it in a 1959 article titled “The French Army and La Guerre Révolutionnaire,” published in the Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. From those early writings, Paret developed a fascination for the new military approach, and, as a frequent contributor to the Princeton Studies in World Politics, often highlighted the emerging strategies and debates surrounding counterinsurgency theory and practice.2

In his book French Revolutionary Warfare from Indochina to Algeria: The Analysis of a Political and Military Doctrine, published in 1964, Paret examined both the tenets of revolutionary insurgency that anticolonial revolutionaries were developing in Indochina and North Africa, as well as the emerging doctrine of counterrevolutionary war that French commanders were refining on the ground. In Paret’s view—a view shared by many scholars and practitioners at the time—the revolutionary strategies had their source in the writings and practices of Mao Zedong. Most of the French pioneers of counterrevolutionary methods had turned to Mao to get their bearings, and did so very early—for instance, in 1952 already, General Lionel-Max Chassin published La conquête de la Chine par Mao Tsé-Toung (1945–1949), which would lay the groundwork for modern warfare theory.3

A founding principle of revolutionary insurgency—what Paret referred to as “the principal lesson” that Mao taught—was that “an inferior force could outpoint a modern army so long as it succeeded in gaining at least the tacit support of the population in the contested area.”4 The core idea was that the military battle was less decisive than the political struggle over the loyalty and allegiance of the masses: the war is fought over the population or, in Mao’s words, “The army cannot exist without the people.”5

As a result of this interdependence, the insurgents had to treat the general population well to gain its support. On this basis Mao formulated early on, in 1928, his “Eight Points of Attention” for army personnel:

1. Talk to people politely.

2. Observe fair dealing in all business transactions.

3. Return everything borrowed from the people.

4. Pay for anything damaged.

5. Do not beat or scold the people.

6. Do not damage crops.

7. Do not molest women.

8. Do not ill-treat prisoners-of-war.6

Two other principles were central to Mao’s revolutionary doctrine: first, the importance of having a unified political and military power structure that consolidated, in the same hands, political and military considerations; and second, the importance of psychological warfare. More specifically, as Paret explained, “proper psychological measures could create and maintain ideological cohesion among fighters and their civilian supporters.”7

Revolutionary warfare, in Paret’s view, boiled down to a simple equation: Guerrilla warfare + psychological warfare = revolutionary warfare.8 And many revolutionary strategies fell under the rubric of psychological warfare, Paret maintained, including at one end of the spectrum terrorist attacks intended to impress the general population, and at the other end, diplomatic interventions at international organizations. In all of these strategies, the focus was on the population, and the medium was psychological. As Paret wrote:

The populace, according to the formulation by Mao Tse-tung that has become one of the favorite quotations of the French theorists, is for the army what water is for fish. And more concretely, “A Red army… without the support of the population and the guerrillas would be a one-armed warrior.” The conquest—i.e., securing complicity—of at least sections of the population is accordingly seen as the indispensable curtain-raiser to insurrectional war.9

Or more succinctly, drawing on a detailed five-stage process elaborated by another French analyst: “the ground over which the main battle will be fought: the population.”10

Of course, neither Paret nor other strategists were so naïve as to think that Mao invented guerrilla warfare. Paret spent much of his research tracing the antecedents and earlier experiments with insurgent and counterinsurgency warfare. “Civilians taking up arms and fighting as irregulars are as old as war,” Paret emphasized. Caesar had to deal with them in Gaul and Germania, the British in the American colonies or in South Africa with the Boers, Napoleon in Spain, and on and on. In fact, as Paret stressed, the very term “guerrilla” originated in the Spanish peasant resistance to Napoleon after the Spanish monarchy had fallen between 1808 and 1813. Paret developed case studies of the Spanish resistance, as well as detailed analyses of the repression of the Vendée rebellion at the time of the French Revolution between 1789 and 1796.11 Long before Mao, Clausewitz had dedicated a chapter of his famous work On War to irregular warfare, calling it a “phenomenon of the nineteenth century”; and T. E. Lawrence as well wrote and analyzed key features of irregular warfare after he himself had led uprisings in the Arab peninsula during World War I.

But for purposes of describing the “guerre révolutionnaire” of the 1960s, the most pertinent and timely objects of study were Mao Zedong and the Chinese revolution. And

on the basis of that particular conception of revolutionary war, Paret set forth a model of counterrevolutionary warfare. Drawing principally on French military practitioners and theorists, Paret delineated a three-pronged strategy focused on a mixture of intelligence gathering, psychological warfare on both the population and the subversives, and severe treatment of the rebels. In Guerrillas in the 1960’s, Paret reduced the tasks of “counterguerrilla action” to the following:

1. The military defeat of the guerrilla forces.

2. The separation of the guerrilla from the population.

3. The reestablishment of governmental authority and the development of a viable social order.12

Paret emphasized, drawing again on Mao, that military defeat is not enough. “Unless the population has been weaned away from the guerrilla and his cause, unless reforms and re-education have attacked the psychological base of guerrilla action, unless the political network backing him up has been destroyed,” he wrote, “military defeat is only a pause and fighting can easily erupt again.” Rehearing the lessons of the French in Vietnam and Algeria, and the British in Malaysia, Paret underscored that “the tasks of counterguerrilla warfare are as much political as military—or even more so; the two continually interact.”13

So the central task, according to Paret, was to attack the rebel’s popular support so that he would “lose his hold over the people, and be isolated from them.” There were different ways to accomplish this, from widely publicized military defeats and sophisticated psychological warfare to the resettlement of populations—in addition to other more coercive measures. But one rose above the others for Paret: to encourage the people to form progovernment militias and fight against the guerrillas. This approach had the most potential, Paret observes: “Once a substantial number of members of a community commit violence on behalf of the government, they have gone far to break permanently the tie between that community and the guerrillas.”14 In sum, the French model of counterrevolutionary warfare, in Paret’s view, had to be understood as the inverse of revolutionary warfare.

The main sources for Paret’s synthesis were the writings and practices of French commanders on the ground, especially Roger Trinquier and David Galula, though there were others as well.15 Trinquier, one of the first French commanders to theorize modern warfare based on his firsthand experience, had a unique military background. He had remained loyal to the Vichy government in Indochina during World War II, resulting in deep tensions with General Charles de Gaulle and other Free French officers after the war. But he was retained and respected because of his antiguerrilla expertise. Trinquier became especially well-known for his guerrilla-style antiguerrilla tactics during the war in Indochina. He led anti-Communist guerrilla units deep inside enemy territory, and ultimately, by 1951, received command over all of the behind-the-line operations. He was, according to the war correspondent Bernard Fall, the perfect “centurion”: he “had survived the Indochina war, had learned his Mao Tse-tung the hard way, and later had sought to apply his lessons in Algeria or even in mainland France.”16

In his book Modern Warfare: A French View of Counterinsurgency, published in France in 1961 and quickly translated into English in 1964, Trinquier announces a new warfare paradigm and at the same time sounds an alarm. “Since the end of World War II, a new form of warfare has been born,” Trinquier writes. “Called at times either subversive warfare or revolutionary warfare, it differs fundamentally from the wars of the past in that victory is not expected from the clash of two armies on a field of battle.” The failure to recognize this difference, Trinquier warns, could only lead to defeat. “Our military machine,” he cautions, “reminds one of a pile driver attempting to crush a fly, indefatigably persisting in repeating its efforts.” Trinquier argues that this new form of modern warfare called for “an interlocking system of actions—political, economic, psychological, military,” grounded on “Countrywide Intelligence.” As Trinquier emphasizes, “since modern warfare asserts its presence on the totality of the population, we have to be everywhere informed.” Informed, in order to know and target the population and wipe out the insurgency.17

The other leading counterinsurgency theorist, also with deep firsthand experience in Algeria, David Galula, also understood the importance of total information and of winning the hearts and minds of the general population.18 He too had learned his Mao—including the fly analogy, which he quoted in the introduction to his book Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, published in 1964: “In the fight between a fly and a lion, the fly cannot deliver a knockout blow and the lion cannot fly.” In the late 1940s, Galula had closely studied Mao’s writings in their English translation in the Marine Corps Gazette, and, according to people close to him, “spoke of Mao and the civil war ‘all the time.’”19

From Mao, Galula drew the central lesson that societies were divided into three groups and that the key to victory was to isolate and eradicate the active minority in order to gain the allegiance of the masses. Galula emphasizes in Counterinsurgency Warfare that the central strategy of counterinsurgency theory “simply expresses the basic tenet of the exercise of political power”:

In any situation, whatever the cause, there will be an active minority for the cause, a neutral majority, and an active minority against the cause.

The technique of power consists in relying on the favorable minority in order to rally the neutral majority and to neutralize or eliminate the hostile minority.20

The battle was over the general population, Galula emphasized in his Counterinsurgency Warfare, and this tenet represented the key political dimension of a new warfare strategy.

US general David Petraeus picked up right where David Galula and Peter Paret left off. Widely recognized as the leading American thinker and practitioner of counterinsurgency theory—eventually responsible for all coalition troops in Iraq and the architect of the troop surge of 2007—General Petraeus would refine Galula’s central lesson to a concise paragraph in the very first chapter of his edition of the US Army and Marine Corps Field Manual 3-24 on counterinsurgency, published and widely disseminated in 2006. Under the header “Aspects of Counterinsurgency,” Petraeus’s field manual reads:

In almost every case, counterinsurgents face a populace containing an active minority supporting the government and an equally small militant faction opposing it. Success requires the government to be accepted as legitimate by most of that uncommitted middle, which also includes passive supporters of both sides. (See Figure I-2.)21

The referenced figure captures the very essence of this way of seeing the world, echoing Galula exactly: “In any situation, whatever the cause.” From Mao and Galula, Petraeus derived not only the core foundations of counterinsurgency, but a central political vision. This is a political theory, not simply a military strategy. It is a worldview, a way of dealing with all situations—whether on the field of battle or off it.22

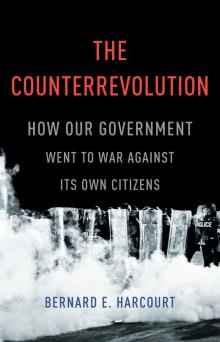

Figure 1-2 from General Petraeus’s Counterinsurgency Field Manual.

On this political foundation, General Petraeus’s manual establishes three key pillars—what might be called counterinsurgency’s core principles.

The first is that the most important struggle is over the population. In a short set of guidelines that accompanies his field manual, General Petraeus emphasizes: “The decisive terrain is the human terrain. The people are the center of gravity.” David Galula had said the same. “The objective is the population,” Galula wrote. “The population is at the same time the real terrain of the war.”23 This first lesson had been learned the hard way in Algeria for the French, and later in Vietnam for the Americans. Galula had made the point in his 1963 memoirs, emphasizing that “support from the population was the key to the whole problem for us as well as for the rebels.” But eventually the lesson was learned, and the general population would become central to counterinsurgency theory. In a short “Summary,” General Petraeus’s field manual stresses that “at its core, COIN [counterinsurgency] is a struggle for the population

’s support.”24 The main battle, then, is over the populace.

The second principle is that the allegiance of the masses can only be secured by separating the small revolutionary minority from the passive majority, and by isolating, containing, and ultimately eliminating the active minority. In his accompanying guidelines, General Petraeus emphasizes: “Seek out and eliminate those who threaten the population. Don’t let them intimidate the innocent. Target the whole network, not just individuals.”25

The third core principle is that success turns on collecting information on everyone in the population. Total information is essential to properly distinguish friend from foe and then extract the revolutionary minority. It is intelligence—total information awareness—that renders the counterinsurgency possible. It is what makes the difference between, in the words of General Petraeus’s field manual, “blind boxers wasting energy flailing at unseen opponents and perhaps causing unintended harm,” and, on the other hand, “surgeons cutting out cancerous tissue while keeping other vital organs intact.”26

Heavily influenced by Galula’s writings—as well as by those of the British counterinsurgency theorist Sir Robert Thompson—Petraeus’s field manual reads like an ode to early French counterinsurgency theory.

“Counterinsurgency is not just thinking man’s warfare—it is the graduate level of war,” states the epigraph to the first chapter of General Petraeus’s manual. And for Petraeus, the graduate level was 1960s French counterinsurgency strategy as reflected in its most theoretical manifestations. Building on his extensive firsthand experience, General Petraeus gravitated toward those early writings and emphasized the political nature of the battle.

The Counterrevolution

The Counterrevolution